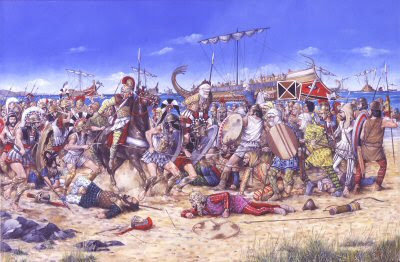

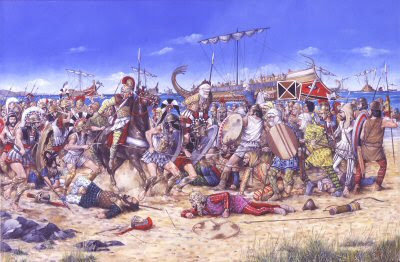

Battle of Marathon by Brian Palmer.

The Battle of Marathon 490 BC during the Persian Greek Wars. King Darious I of Persia sent his son in law Mardonius to invade Greece in 492 BC. The Persian Forces conquered Thrace and Macedonia before their fleet was devastated by a storm. Mardonia was forced to return to Asia. A second Persian invasion force crossed the Aegean sea. After conquering Eretria, the Persian Army under Datis (15,000 strong) landed near Marathon. (Marathon is 24 miles northeast of Athens.) General Miltiades, general in the Greek army gathered a force of 10,000 Athenians and 1,000 Plataean citizen Soldiers.

The ancient world was characterised by a number of epic struggles between mighty civilisations; Egypt vs Nubia, Rome vs Carthage, Greece vs Persia. The last of these had a major impact on the subsequent course of Western history, as the eventual victory of the Greeks allowed them to maintain their independence for another 300 years, during which time Greek culture and science flowered into the period now known as the Golden Age, helping to determine the shape of subsequent Western culture and thought.

Among the key incidents in the history of the conflict between the Persian Empire and the Greek city-states it sought to subdue were the disastrous fates that befell enormous Persian fleets no less than three times. According to ancient sources literally hundreds of ships and thousands of men sank to the bottom of the Aegean, where high rates of deposition of protective silt may well have preserved them for two-and-half millennia, offering a treasure trove of unparalleled archaeological significance to anyone who can locate them.

Darius and Xerxes

In the 5th century BCE the Persian Empire had conquered most of the known world and incorporated lands from the Himalayas to the Balkans, from the Upper Nile to the shores of the Caspian. Under the Persian aegis fell several of the Greek city-states of Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), while the actions and attitude of the independent states of the Greek mainland irked the Persian emperors. Greek states such as Athens and Eretria had meddled in the affairs of Asia Minor, fomenting rebellions against the Persian overlords, and Darius the Great, emperor of Persia, determined to punish them. In 492 BCE he dispatched an army under his general and son-in-law Mardonius.

The sea monsters of Athos

Mardonius crossed the Hellespont that separated Asia Minor from Europe and marched down the Aegean coast of Greece, accompanied by a mighty fleet to offer naval and logistical support. The fleet sailed across the Aegean to the mainland and followed the coast down to Acanthus. To progress further it needed to detour around the peninsula of Mount Athos, which jutted out into the sea. According to Herodotus, whose Histories are the primary source for the Greco–Persian war, as the fleet ‘made to double Mount Athos’:

A violent North wind sprang up, against which nothing could contend, and handled a large number of the ships with much rudeness, shattering them and driving them aground upon Athos. It is said that the number of the ships destroyed was little short of 300; and the men who perished were more than 20,000. For the sea about Athos abounds in monsters beyond all others; and so a portion were seized and devoured by these animals, while others were dashed violently against the rocks; some, who did not know how to swim, were engulfed; and some died of the cold.

Without naval support Mardonius was forced to turn back and the invasion was postponed for two years. The Persian’s second invasion, in 490 BCE, was no more successful, and before he could plan a third attempt Darius died. It was left to his successor Xerxes to punish the upstart Greek states.

The greatest force the world had ever seen

By 480 BCE Xerxes had gathered what was probably the largest army in human history up to that point. It was said that he wept upon witnessing the serried ranks, overcome by the thought that within a few decades so many men would no longer be alive. The ancient estimates are probably wildly exaggerated – one speaks of the total land and sea forces numbering 2,641,610 men, accompanied by the same number of camp followers and hangers-on, giving more than 5 million people. Modern scholars scoff at these estimates, and it is widely assumed that they are out by a factor of ten. Nonetheless, Xerxes’ army was unprecedented in scale and diversity, comprising warriors from 46 different nations, including many Greek states and colonies that were inimical to the mainland alliance of Athens and Sparta, which led the Greek resistance.

Accompanying the army was a vast fleet, said to number 1,207 triremes (battle galleys propelled by three rows of oars) and countless smaller support, troop transport and cargo vessels. The ships were drawn from Phoenicia, Egypt, Cyprus and Asia Minor, including many of the Greek states under Persian control, and therefore represented a unique cross-section of naval technology and design of the period.

The Magnesian disaster and the Hollows of Euboea

Determined to take no chances with the treacherous waters off Mount Athos, Xerxes had had a canal dug across the isthmus that separated the mountain from the mainland. He had decreed that it should be wide enough to admit two galleys abreast, and the work took two years. Ultimately this extravagant gesture was to little avail – although the fleet successfully negotiated the Athos peninsula, large numbers of ships were lost in two massive storms.

One struck the fleet as it was anchored off the coast of Magnesia in an unfavourable location where there was room for only a few ships in the relative safety of the bay, forcing the others to moor in rows eight deep, which left the outermost ships stuck far out to sea. When a fierce east wind blew up in the morning, only a few of the ships could be dragged up to safety on the beach. According to Herodotus, the ships caught in the open sea were exposed to the gale and dashed against the rocks and coast at Pelion, Cape Sepias,Meliboea and Casthanaea.

The Greeks put this stroke of good fortune (from their point of view) down to the intercession of Boreas, god of the north wind. Divine providence or not, the disaster cost the Persians both ships and loot. Herodotus tells us:

The most conservative estimate of how many ships were lost in this disaster is 400, along with innumerable personnel, and so much valuable property that a Magnesian called Ameinocles the son of Cretines, who owned land near Sepias, profited immensely from this naval catastrophe. In the following days and months gold and silver cups were washed ashore in large numbers for him to pick up; he also found Persian treasure-chests, and in general became immensely wealthy.

While the main body of the fleet was suffering off the Magnesian coast, a detached squadron of 200 ships was attempting to round Euboea to outflank the Greek fleet. They too suffered from the storm. According to Herodotus the high winds smashed the ships against the shoreline known as the ‘Hollows of Euboea’, and all 200 of the galleys were lost.

In practice neither of these disasters made too much of a dent in the Persian fleet, vast as it was, but they helped to prevent it from gaining a tactical advantage over the outnumbered Greek navy, which got the better of subsequent naval engagements, including a battle in the Artemision Channel in which many Persian galleys were destroyed. These naval victories halted the Persian advance and effectively ended Xerxes’ hopes of a swift and crushing victory in the war as a whole. Without naval support, Xerxes felt compelled to pull the bulk of his forces out of the Balkans, leaving Mardonius to pursue the war, which proved beyond him. Eventually the Persians were forced out of Greece forever.

Aegean treasure

Even if Herodotus was exaggerating the numbers of galleys and men involved and the numbers lost during the Persian invasions, the potential value of the wrecked fleets could be huge. There could be the remains of hundreds of ships, thousands of men and huge quantities of weapons, armour, stores and supplies and loot of all types resting at the bottom of the Aegean. All of it dates back 2,500 years to a period about which there is scant archaeological evidence, at least for ships and naval technology. The size and diversity of the Persian invasion forces mean that the remains would offer a unique picture of peoples and military and naval technology, not just from Persia and Greece but from across the ancient world. For the acquisitive there is also the promise of large quantities of precious objects and precious metals, like the ‘gold and silver cups … and Persian treasure chests’ mentioned by Herodotus.

The ultimate prize for archaeologists, however, would be the discovery of the wreck of a trireme, the large galleys that constituted ships of the line for ancient navies. No trireme has ever been found, and historians are still in the dark about many aspects of this potent ancient naval technology. When a replica trireme was constructed, for instance, it was found that it could not match the performance capabilities ascribed to ancient galleys, which were much faster than modern experts are able to explain. Finding one of 1,000+ plus sunken galleys of the Persian invasion fleets could help to resolve decades of academic disputes. According to Dr Robert Hohlfelder, a maritime archaeologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder: ‘Underwater archaeologists have wish lists. A trireme is certainly one of the top ones on most people’s lists. And I think this [the waters off Mount Athos] is one of the best places to look for them.’

However, there are reasons why trireme remains have proved so elusive. Since ancient galleys did not use ballast, they did not sink when wrecked but floated on the surface. Ancient sources record how they were salvaged simply by being towed back to land, where they were either repaired or recycled for other purposes. Cargo would sometimes act as ballast, dragging a ship to the bottom, which is why ancient cargo ships have been recovered, but triremes were war galleys and hence did not carry heavy cargoes in their hold. The heaviest part of the trireme was probably the bronze ram on the prow that was used to smash enemy ships, and these may be lying on the bottom of the Aegean awaiting recovery, along with metal arms and armour carried by those on board.

Preserved in the deep

The Mediterranean is one of the most intensively exploited seas in the world, and has been so for millennia. This applies to treasure hunting and looting of wrecks, and there is considerable concern that many of the best/most accessible ancient wrecks have already been stripped of anything valuable, damaging and rendering them useless for archaeology in the process. Similarly, the prevalence of dragnet trawling, where fishermen drag heavily weighted booms with attached nets along the bottom of the sea, destroying everything in their path, has probably damaged or obliterated many ancient wrecks.

But the experts hope that the context of the Persian fleet wrecks may have preserved them from the looters. The fleets came to grief in deep water, especially the biggest potential wreck focus, off Mount Athos, where the sea bottom drops sharply to depths of 600 metres (2,000 feet) or more. This area is also quite remote, which should have helped to protect it from looters. An additional benefit is that silt is deposited quite fast in the Aegean, so that any remains may have been rapidly covered in a layer of preserving and protective silt.

Looking for the Persian fleets

In recent years the story of the Persian fleets has gained a new profile thanks to a concerted international effort to locate and study the wrecks, an effort made possible by new technology. The Persian Wars Shipwreck Survey (PWSS) – a joint programme by the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research and the Canadian Archaeological Institute at Athens, together with various other academics and institutions – uses side-scan sonar, mini-submarines and submarine remote-operated vehicles (ROVs) to map and explore the locations described by Herodotus.

In its three seasons of exploration so far the PWSS has explored the waters off the Mount Athos peninsula, the Hollows of Euboea (off the coast of southern Euboea) and the Artemision Channel, site of a major naval battle. The results have not been breathtaking. So far one of the main discoveries has been the location of the wreck of a cargo ship off Mount Athos, which was carrying amphorae identified as being from Mende, a Greek city to the west of Mount Athos. This could mean that the ship had nothing to do with Darius’ fleet (it could date from up to a century earlier), or it could have been a supply ship carrying material requisitioned by the Persian invaders.

The headline discovery, however, has been attributed to the help of an octopus, likened to one of Herodotus’ ‘monsters beyond all others’. Alerted to the fact that local fishermen hauling in their catch had chanced upon two bronze helmets from the classical period (500–323 BCE), the PWSS crew searched in the same area and spotted a large jar on the seabed. The jar was home to an octopus, a creature renowned for occasionally retrieving sunken objects and squirreling them away in its lair. Sure enough, the octopoid loot proved to include a bronze sauroter – a pointed spear butt or butt-spike that fitted onto the end of a Greek hoplite’s (infantryman) spear, allowing it to be stuck into the ground and also making it a double-ended weapon. Finding the weapon accessory where two pieces of armour have also been recovered has strengthened belief that the wrecks of the Persian fleet (which included many Greek soldiers from the vassal states in Asia Minor, as well as from Greek states inimical to Athens and Sparta) do lie in the area.

The PWSS team has had less luck in the waters around Euboea, but it plans to return in 2006 to continue mapping the sea floor and looking for promising targets to investigate using its submersibles. It also warns, however, that academics are not the only ones equipped with such technology. Katerina Dellaporta, director of underwater antiquities for Greece and one of the survey’s leaders, has warned, ‘Before, looters would only do scuba diving. But now, the technology [such as ROVs] allows everybody to have access to deeper waters.’ While the assertion that ‘everybody’ might get access to deep water is perhaps an overstatement (buying and operating an ROV costs tens–hundreds of thousands), it is to be hoped that archaeologists and not looters are the first to locate the lost wrecks of the great fleets of Darius and Xerxes.

LINK