Alexander von Humboldt, Vegetation zones on Mount Chimborazo (Alexander von Humboldt and A.G. Bonpland, Geographie der Pflanzen in den Tropenländern, ein Naturgemälde der Anden, gegründet auf Beobachtungen und Messungen, welche vom 10. Grade nördlicher bis zum 10. Grade südlicher Breite angestellt worden sind, in den Jahren 1799 bis 1803, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Kartenabteilung).

Peter J. Bowler

Why was Charles Darwin so eager to join H.M.S. Beagle on its voyage to South America? Part of the answer lies in the fact that as a student at Cambridge he had been enthralled by Alexander von Humboldt's writings about South America. Darwin longed to follow Humboldt on a voyage to the tropics. He was inspired by Humboldt's vision of a new science that would uncover the multitude of relationships maintaining Earth's physical structure and governing the lives of its plant, animal, and human inhabitants.

Nor was he the only one to be inspired. A whole generation of naturalists participated in what historians have called "Humboldtian science" (1-3). This was a project to measure and map every feature of the Earth, with the aim not of mere description but of throwing light on the ways in which physical and organic processes interact to sustain and develop the world in which we live. The Humboldtian vision was not a static one: It incorporated the new science of geology, which explained how the current state of Earth and its inhabitants had been formed by natural processes. In this important respect, Darwin's theory of evolution, in which populations are shaped by adaptation to an ever-changing world, was a direct (if unanticipated) product of Humboldtian science. Modern efforts to create a science of the environment also derive from this vision.

Humboldt straddled the transition from the 18th-century Age of Enlightenment to the Romantic era of the early 19th century. Historians still debate his position within the cultural developments of the time (4-6). His vision of nature as a complex system of interactions that we perceive through the imagination as well as the senses certainly resonates with the Romantic worldview of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, whom Humboldt knew and admired (6, 7). For Humboldt, humanity's perception of nature's unity and power was as much aesthetic as it was rational, a visionfar more in tune with Romanticism than with the dry natural theology of Darwin's mentors.

But his passion for precise description and accurate measurement reflects the more rationalist attitude of the Enlightenment (4, 5, 8). His concern for the predicament of the human inhabitants of the regions he visited has led some to see him as a political radical, in the tradition of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. In the end, he defies assignment to any of the neat categories erected by historians, and perhaps it is this versatility that allowed him to influence so many later developments.

Humboldt was born in Berlin on 14 September 1769. He studied at the universities of Frankfurt and Göttingen, and then moved on to the mining academy of Freiburg in Saxony. Here he came under the influence of the geologist Abraham Gottlob Werner, who was pioneering the study of what we would now call the stratigraphic column. Through years of study, diplomatic work, and as a leader of the Prussian mining service, Humboldt expanded his knowledge of geology. He became interested in the structure of mountains and longed to make a detailed study of volcanoes.

Humboldt recognized that mountains were created by earth movements and volcanism after the sedimentary rocks were laid down, in effect rejecting the strict "Neptunism" of Werner's theory in which deposition from water was theonly agent of change. As did many European geologists, however, he still considered himself a follower of the Wernerian method. Incorporating a role for volcanism did not upset the project to define the sequence of events defining Earth's history: It merely made that history more complex. He identified the stratigraphic position of a distinctive formation that he called the Jura limestone, which was subsequently incorporated by Leopold von Buch into the Jurassic system.

In 1790, Humboldt visited Paris with Georg Forster, who had been a naturalist on Captain James Cook's second voyage. As an ardent liberal, Humboldt was full of praise for the achievements of the French Revolution. After 1796, he became financially independent and continued his studies at Jena, where he met Goethe and Friedrich Schiller. He performed painful experiments on himself in an effort to demonstrate the role of electricity as the life-force. He was also learning the techniques of geodetic and geophysical measurement, because by now he had conceived the project to create "une physique du monde"--a global science based on careful measurement and on the paradigm that all natural forces interact harmoniously to sustain the whole.

Humboldt was anxious to explore outside Europe and planned a trip to North Africa. While waiting to take a ship at Marseilles he was informed that Tunis was unsafe to visit. He decided instead to journey into Spain, where he prepared the first relief map of the region. In Madrid, he attended the royal court and obtained permission to visit the Spanish colonies in South America.

Accompanied by the botanist Aimé Bonpland, he arrived in what is now Venezuela in July 1799 and spent the next 5 years exploring the continent, often enduring considerable hardships. Everywhere the two explorers went, they collected plants and took measurements of temperature, air pressure, and Earth's magnetic field. They navigated the Orinoco river and confirmed the existence of a connection between the Orinoco and the Amazon. Throughout the trip Humboldt took notes on the conditions of the human inhabitants, and made a particular study of the economics and politics of Mexico.

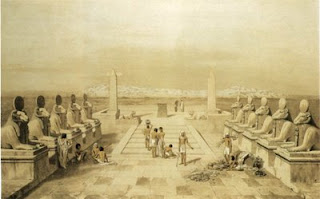

In June 1802, Humboldt set out to climb the volcanic mount Chimborazo in the Andes, then thought to be the highest mountain in the world. Although they did not reach the summit, Humboldt and his party ascended to nearly 20,000 feet, the highest point then reached by any European mountaineer. Humboldt was now convinced that volcanoes form in regular lines along fissures in Earth's crust.

In 1804, Humboldt paid a brief visit to the United States before returning to Europe. After further travels in Germany and Italy he settled down in Paris, where he remained until 1827. Here he prepared his results for publication, eventually bankrupting himself because of the enormous cost of producing maps and illustrations. He returned to Berlin to serve as an adviser to the government. He had long wanted to explore Asia to compare the region with what he had observed in South America. When invited by the Czar to explore Russia in 1829, he was able to extend the trip into a major survey of Siberia.

In his publications, Humboldt described a vast range of phenomena, stressing the interactions between the physical, organic, and human worlds. He also pioneered new ways of mapping and depicting relationships (4).Humboldt used cross sections to illustrate the diversity of terrain across extended landmasses. A famous diagram of Chimborazo, published in his Essai sur la geographie des plantes of 1807, describes the zones of vegetation at successive levels, showing how altitude could affect the local climate (6). In 1817, Humboldt introduced the concept of the isotherm to link areas with similar temperatures on a map, again showing how altitude and latitude affected the climate.

It was the interaction of the general with the particular that so fascinated Humboldt. He wanted to understand the general laws of nature, but he knew that the processes governed by those laws were shaped by the local environment in a host of ways not anticipated by earlier naturalists. Yet all these diverse phenomena were integrated into a harmonious whole, and it was Humboldt's aim to understand the relationships involved. To some scholars, this ambition reveals his commitment to the Romantic vision of nature.

At the same time, Humboldt was concerned with the significance to humans of the natural environment. He was ever alert to the ways in which political structures interfered with the ways in which the inhabitants of a region sought to gain their livelihoods. Nicolaas Rupke argues that it was his political and economic study of Mexico, published between 1808 and 1811, that did most to bring him to the world's attention--and this was more a product of Enlightenment liberalism than of Romanticism (5).

But throughout his work, Humboldt stressed how human values shape our perception of nature, in effect becoming the model through which our vision of the world is constructed (9). His Ansichten der Natur (Views of Nature) of 1808 offered an "aesthetic treatment of natural history"--part travel book, part celebration of the diversity of natural phenomena, but all presented to inspire as well as inform. His last great work, Kosmos (1845 to 1862), included accounts of the history of science and discussions of the significance of changing artistic perceptions of nature, especially in landscape painting (10). These elements reveal a focus on the human dimension in science that leftHumboldt increasingly isolated from the scientific community in his later years. He died on 6 May 1859.

Humboldt stressed how human values shape our perception of nature, in effect becoming the model through which our vision of the world is constructed. It was the more empirical aspects of "Humboldtian science" that inspired Darwin and his generation to think about the world in a more interactive way (1, 3). Humboldt's plant geography encouraged Alphonse de Candolle and, through him, a later generation of biologists, who would found what we now call ecology (2). His work in geology and geophysics served as a model for the geological and other surveys that became an important component of mid-19th-century science.

Humboldt had openly appealed to the Royal Society of London and the British Association for the Advancement of Science to lobby the British government for the creation of a world-wide chain of magnetic observatories. Under the direction of Sir Edward Sabine, stations were established in Montreal, Tasmania, the Cape of Good Hope, and Bombay, and Sir James Ross commanded a naval expedition to the Antarctic. Ross located the magnetic south pole, and Sabine's coordinated observations eventually revealed the link between magnetic storms and sunspot activity.

And, of course, Darwin was inspired to visit the tropics, leading to his decision to join the Beagle, his discoverieson the Galapagos islands, and his theory of natural selection. Darwin drew on a variety of sources, but Humboldt's influence, together with that of Charles Lyell, formed the basis of his conviction that the driving force of organic change is the complex web of interactions by which a population adapts to its ever-changing local environment.

Darwin, too, linked the human species into nature. But his theory turned Humboldt's vision on its head as effectively as it demolished the natural theology of William Paley. Despite his lack of explicit religious commitment, Humboldt saw the world as a unified whole whose structure is best revealed by the human imagination. If this vision of nature was Romantic rather than Christian in origin, it was equally vulnerable to the process of erosion begun by the evolutionists. For Darwin, the natural processes of evolution had created the human mind and shaped the way it perceived the world. Humans were not the centerpiece of creation, nor was their aesthetic response to the world a significant factor to be taken into account in the development of a scientific explanation of its origin and structure.

Darwin explored the same complex of interactions as Humboldt, but created a darker picture in which we were the products of forces that owe nothing to our values or our imagination. The mid-19th century's fascination with the idea of progress was in some respects a desperate attempt to retain a special role for humanity as the goal of creation. This was a role which Humboldt had taken for granted but which Darwinism threatened to undermine.

References and Notes

- S. F. Cannon, Science in Culture: The Early Victorian Period (Science History Publications, New York, 1978).

- M. Nicolson, Hist. Sci. 25, 167 (1987).

- P. J. Bowler, The Earth Encompassed: A History of the Environmental Sciences (Norton, New York, 1993).

- A. M. C. Godlewska, in Geography and Enlightenment, D. N. Livingstone and C. W. J. Withers, Eds. (Univ. of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1999), pp. 236-275.

- N. Rupke, in Geography and Enlightenment, D. N. Livingstone and C. W. J. Withers, Eds. (Univ. of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1999), pp. 319-339.

- M. Nicolson, in Romanticism and the Sciences, A. Cunningham and N. Jardine, Eds. (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1990), pp. 169-185.

- M. Bowen, Empiricism and Geographical Thought: From Francis Bacon to Alexander von Humboldt(Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1981).

- D. N. Livingstone, The Geographical Tradition: Episodes in the History of a Contested Enterprise (Blackwell, Oxford, 1992).

- M. Dettelbach, in Visions of Empire: Voyages, Botany, and Representations of Nature, D. P. Miller and P. H. Reill, Eds. (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1996), pp. 258-292.

- A. von Humboldt, Cosmos, reprint of vol. 1, introduction by N. Rupke (Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore, MD, 1997).

- Portrait by F. Georg, exhibited at Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Reprinted with permission.

P. J. Bowler is in the History of Science Program, School of Anthropological Studies, Queen's University, Belfast BT7 1NN, UK.