The archaic...the arcane...and fantastic...the historic...Compiled from divers sources.

Showing posts with label Expedition. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Expedition. Show all posts

Monday, June 8, 2015

Nepenthes attenboroughii digesting shrew on Mount Victoria, Palawan, Philippines

Nepenthes attenboroughii, or Attenborough's pitcher plant, is a montane species of carnivorous pitcher plant of the genus Nepenthes. It is named after the celebrated broadcaster and naturalist Sir David Attenborough, who is a keen enthusiast of the genus. The species is characterised by its large and distinctive bell-shaped lower and upper pitchers and narrow, upright lid. The type specimen of N. attenboroughii was collected on the summit of Mount Victoria, an ultramafic mountain in central Palawan, the Philippines.

Mount Victoria (1726 or 1709 m ), or Victoria Peaks, is a mountain in central Palawan, Philippines, that lies within the administrative Municipality of Narra. The mountain, which includes the twin peaks known as "The Teeth", as well as the single prominence known as "Sagpaw", form the largest contiguous land area and second highest portion of the Mount Beaufort Ultramafics geological region, a series of ultramafic outcrops of Eocene origin, that includes Palawan's highest peak, Mount Mantalingahan (2085 m).

The summit flora of Mount Victoria includes Leptospermum sp., Medinilla spp., Pleomele sp., Vaccinium sp., various grasses, as well as the sundew Drosera ultramafica, which grows at similar elevations to N. attenboroughii.

The pitcher plant is among the largest of all pitchers and is so big that it can catch rats as well as insects in its leafy trap.

During the same expedition, botanists also came across strange pink ferns and blue mushrooms they could not identify.

The botanists have named the pitcher plant after British natural history broadcaster David Attenborough.

They published details of the discovery in the Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society earlier this year.

Word that this new species of pitcher plant existed initially came from two Christian missionaries who in 2000 attempted to scale Mount Victoria, a rarely visited peak in central Palawan in the Philippines.

With little preparation, the missionaries attempted to climb the mountain but became lost for 13 days before being rescued from the slopes.

On their return, they described seeing a large carnivorous pitcher plant.

That pricked the interest of natural history explorer Stewart McPherson of Red Fern Natural History Productions based in Poole, Dorset, UK and independent botanist Alastair Robinson, formerly of the University of Cambridge, UK and Volker Heinrich, of Bukidnon Province, the Philippines.

All three are pitcher plant experts, having travelled to remote locations in the search for new species.

So in 2007, they set off on a two-month expedition to the Philippines, which included an attempt at scaling Mount Victoria to find this exotic new plant.

Accompanied by three guides, the team hiked through lowland forest, finding large stands of a pitcher plant known to science called Nepenthes philippinensis , as well as strange pink ferns and blue mushrooms which they could not identify.

As they closed in on the summit, the forest thinned until eventually they were walking among scrub and large boulders.

"At around 1,600 metres above sea level, we suddenly saw one great pitcher plant, then a second, then many more," McPherson recounts.

"It was immediately apparent that the plant we had found was not a known species."

Pitcher plants are carnivorous. Carnivorous plants come in many forms, and are known to have independently evolved at least six separate times. While some have sticky surfaces that act like flypaper, others like the Venus fly trap are snap traps, closing their leaves around their prey.

Pitchers create tube-like leaf structures into which insects and other small animals tumble and become trapped.

The team has placed type specimens of the new species in the herbarium of the Palawan State University, and have named the plant Nepenthes attenboroughii after broadcaster and natural historian David Attenborough.

"The plant is among the largest of all carnivorous plant species and produces spectacular traps as large as other species which catch not only insects, but also rodents as large as rats," says McPherson.

The pitcher plant does not appear to grow in large numbers, but McPherson hopes the remote, inaccessible mountain-top location, which has only been climbed a handful of times, will help prevent poachers from reaching it.

During the expedition, the team also encountered another pitcher, Nepenthes deaniana , which had not been seen in the wild for 100 years. The only known existing specimens of the species were lost in a herbarium fire in 1945.

On the way down the mountain, the team also came across a striking new species of sundew, a type of sticky trap plant, which they are in the process of formally describing.

Thought to be a member of the genus Drosera , the sundew produces striking large, semi-erect leaves which form a globe of blood red foliage.

Labels:

Expedition,

Exploration,

Tree

Thursday, January 31, 2013

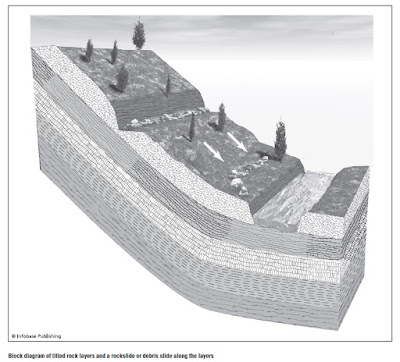

Rockfall and Rockside

rockfall

In contrast to a rockslide, which stays in contact with the

surface throughout its movement, a rockfall is a mass of rocks that breaks

loose from the bedrock and falls through the air to the slope below. Most of

the travel is a free fall, but it may include bouncing as well. Rockfalls

typically break away from the bedrock along steeply inclined joints.

Undercutting of slopes by rivers, wind, or human activities also hastens

rockfalls. Toppling is a particular type of rockfall that involves the rotation

of the rock mass away from the exposure around a fixed fulcrum. Whatever the

mechanism, repeated rockfalls or rockslides produce a pile of rock rubble at

the foot of a cliff or slope. This rubble is called talus. Earthquakes in

mountainous regions produce numerous rockfalls.

rockslide

A mass of solid rock that slides quickly down an inclined

discontinuity. The most common discontinuities are bedding and fractures. In

sedimentary rocks, bedding is usually the primary discontinuity. With bedding,

a rigid layer such as limestone or sandstone typically breaks free and slides

down an underlying, softer layer such as shale. In crystalline rocks (igneous

and metamorphic), the most common discontinuities are joints and faults. The

rock masses may break loose along steeply inclined joints through frost-wedging

processes, but they slide along shallower joints and faults. Rockslides may be

generated by a number of processes, but they are especially common during

earthquakes. The surface waves shake loose otherwise stable rock masses, and

they slide into the valleys below with disastrous results.

Wednesday, November 21, 2012

'Toxic sea' led to Devonian extinction

The researchers say the crustacean was exceptionally well preserved by a combination of processes (Kliti Grice)

Anna Salleh

ABC

Analysis of a 380-million-year-old crab-like fossil from Western Australia has painted a gruesome picture of the events leading to one of Earth's major mass extinctions.

Climate change and a devastating meteorite have both been fingered as causes for the decimation of marine life during the late Devonian period.

But research published in a recent issue of the journal Geology suggests the extinction occurred as a result of a toxic ocean, devoid of oxygen.

"We think there was anoxia, where toxic levels of hydrogen sulfide are released into the zone where light penetrates into the ocean," says organic geochemist Professor Kliti Grice, of Curtin University.

"A modern analogue of the conditions that existed at this time is the Black Sea."

Grice and colleagues, including PhD student Ines Melendez, reached their conclusions after analysing a 380 million-year-old crab-like fossil from the Gogo Formation in Canning Basin, Western Australia.

They identified chemical remains of various biological molecules, known as biomarkers, that helped paint a picture of environmental conditions at the time.

The researchers found a derivative of cholesterol, confirming for the first time that the fossil was the remains of a crustacean.

And they found biomarkers of photosynthesising phytoplankton, which the crustacean would have fed on.

Grice and colleagues also found biomarkers of green sulfur bacteria, also called Chlorobi which would have photosynthesised using hydrogen sulfide instead of water.

She says Chlorobi made a special pigment that enabled them to capture light of longer wavelengths, making it possible from them to survive in the murky waters beneath the bloom of phytoplankton.

"The ocean became stratified with an oxygen layer and an anoxic layer, and where the Chlorobi lived, right at the point where hydrogen sulfide is abundant," says Grice.

Last but not least, the researchers found biomarkers of sulfate-reducing bacteria, which would have lived even deeper down in the ocean and survived by degrading organic matter using sulfate instead of oxygen. This would have been the original source of the hydrogen sulfide on which the Chloribi thrived.

Grice says the condition of the ocean was identical to that which occurred during a later mass extinction at the end of the Permian, the largest extinction event in the past 600 million years.

The crustacean may have sunk to its death at the bottom of the ocean, intoxicated by hydrogen sulphide, says Grice, where it was preserved for hundreds of millions of years.

Preservation

The researchers say the 15-centimetre wide crustacean was exceptionally well preserved by a combination of processes.Grice says the hydrogen sulphide chemically preserved the muscle tissue in the crustacean, as well as organic molecules from the green sulfur bacteria.

"The molecules and the fossil were all preserved by the same mechanism, and that has never been reported in such detail," says Grice.

The fossil was further preserved by a calcium carbonate encasement built by the sulfate-reducing bacteria.

The levels of biomarkers from sulfate-reducing bacteria were particularly high in this encasement, Grice says.

The research was funded by the Australian Research Council.

Thursday, October 4, 2012

TUTAN KHAMUN TOMB’S IMPACT I

Apart from two world wars, the slaughter of millions by

totalitarian regimes and, though less certainly, the extension of Homo sapiens'

dominion to the moon, no single event in the twentieth century had so profound

an impact, nor set up so many resonances, as the discovery of the tomb of

Nebkheperu-Ra Tutankhamun (c. 1333-1323 BC) in the Valley of the Kings in 1922.

The story has been told countless times: how Howard Carter and his employer,

the Earl of Carnarvon, after years of largely fruitless excavation in Egypt, in

virtually the last days of their concession to dig in the Valley came upon the

burial place of the least of the monarchs of the New Kingdom and found it a

treasure trove the like of which the modern world had never seen. At once all

the stories which had entranced generations since storytelling began, of the

finding, in a remote and secret place, of treasures beyond computation, were

given the force of truth.

The effect of the discovery was extraordinary. In the

immediate aftermath of a particularly dreadful conflict which had caused the

deaths of millions, which had destroyed a world which had endured, largely

unchanging, for centuries, and which was the prelude to world-wide repression,

depression and deprivation, the discovery of this golden boy and his

incalculable riches was bound to be an event of great power. It was the more so

since, for the first time, the distant past could be brought to life by the

application of all the techniques of modern publicity and media exploitation.

This last consequence of the discovery has continued without abatement ever

since.

The contents of Tutankhamun's small, hidden tomb, with its

six little rooms-the very modesty of their scale made it easy for a wide public

to identify with them, if not so readily with what they contained-were, in

Carter's word, `wonderful'. The abundance of gold and gilding alone would

ensure that a world increasingly bereft of splendour would respond with wonder

and delight at their revelation. Whilst honesty compels the observer to

acknowledge that some of the objects with which the king was buried were, when

judged by the highest standards of Egyptian art, of dubious taste, some are

superlative: most are of outstanding craftsmanship, even when the design is not

of the happiest.

Tutankhamun's tomb reveals the heights which Egyptian

technique, especially in wood-carving, gilding and the making of fine jewels,

had achieved in the New Kingdom. Workers in precious metals and in a thousand

specialisations were recruited, organised and set to work on the king's

treasury for the afterlife, all to be completed in the seventy days from death

to the final interment in his House of Millions of Years. His tomb was entered

by robbers, probably not long after his burial. For whatever reason they left

hurriedly, and did not return. The tomb was then entirely forgotten until the

twentieth century.

Tutankhamun's paternity is still doubtful, though it is

likely that he was a son of Akhenaten, by one of his lesser wives, not by

Nefertiti. He was a child when he succeeded: a charming object from the tomb,

the golden haft from a walking stick, shows him as a chubby little boy, wearing

the warrior's blue crown and holding himself very upright with his stomach

drawn tightly in, as no doubt his tutors had instructed him. Little is known of

his reign, though it is clear that the priests of Amun who had been

dispossessed by Akhenaten reasserted their authority, moved the capital back to

Thebes, renamed the king, hitherto Tutankhaten, and execrated `the Heretic of

Amarna', cutting away his name wherever it was to be found in inscriptions.

But, though his life was obscure and his reign relatively unimportant, the

excavation of Tutankhamun's tomb gave the world some idea of what it was to be

a king of Egypt.

Part of the significance of the recovery of Tutankhamun, for

his body was preserved as well as his regalia and possessions, was accounted

for by the fact that he was so small a king, amongst the least of the great

monarchs who had enjoyed the Dual Kingship, whose very existence had been

questioned only a short time before Carter found him in the Valley. If the

discovery had been of one of the great Thutmosids or Amenhoteps, for example,

paradoxically the impact might not have been as great as the finding of this

boy, the formulation of whose given name was unique in all the annals of Egypt

before or after his brief lifetime; he died when he was probably about 19 years

old.

Thus this most obscure of the kings of Egypt became the most

familiar of all, his name applied to countless objects, designs, films and

books. It was as if the world had been waiting for his return; the myth of the

Returning King is an enduring one and in Tutankhamun's case it had become

reality. He was the archetype of the Young Prince, the Beautiful Boy, the Puer

Aeturnus, who awaits rebirth constantly in a variety of forms, some benign,

some deeply menacing.

But Tutankhamun was all light. The scenes which showed him,

with his young wife, hunting in the marshes on his skiff and in the myriad of

ushabti figures, some of the finest carvings in the tomb, portray a young

prince, carefree and by no means especially god-like.

The portraits of Tutankhamun in his tomb show a remarkable

consistency which suggests that they are close to actual likeness. He is

represented as quite exceptionally beautiful, an essential quality of the

archetype; following the reign of Akhenaten, when there was some attempt to

represent the royal family naturistically, a practice which continued in

Tutankhamun's lifetime, it can, with reasonable assurance, be assumed that the

portraits show the king much as he was. In later years, had he lived, he would

no doubt have grown as portly as his likely grandfather, Amenhotep III, whom he

somewhat resembles. But Tutankhamun was never to be old.

The circumstances of his burial were remarkable enough. His

mummified body, badly affected by the action of the resins in the process which

was supposed to preserve it, was contained in a series of magnificent gold

coffins, each one with a representation of the king, each subtly different as

though the craftsmen were representing the king in different moods, or, simply,

as he was seen to each. One of the coffins, the second, was probably intended

originally for Smenkhkara and hence is not a portrait of Tutankhamun at all. The coffins, one inside the other, are hugely

bulky; in turn they are contained inside a series of three wooden shrines,

which carry on them a version of the Book of the Dead, the spells and prayers

designed to carry the King safely to the afterlife, which descend ultimately

from the ancient Pyramid Texts, through the Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom.

The shrines are built on the scale of rooms; the outer shrine is notable for

the four exquisite figures of goddesses who stand by them, their wings and arms

outstretched protectively around the king's mummy. Even so small a king as

Tutankhamun could expect to have gods and goddesses at his service.

TUTAN KHAMUN TOMB’S IMPACT II

The gold mask which covered the head of King Tutankhamun is one of the

most familiar of Egyptian icons. The most moving reproduction of the mask is

this photograph, less familiar than those which show it after it was cleaned.

This was the first record of the mask, taken when it was uncovered by Howard

Carter in the king's tomb in the Valley of the Kings. The dust and the remains

of the garlands which were placed in the king's coffin give this image a

living, deeply moving quality.

But the noblest of all the representations of Tutankhamun,

which emphasises his divinity and the majesty of his office, is the immense

gold mask which was placed over the head of his mummy, in the innermost of the

coffins; after the Pyramids it is perhaps the most universally reproduced of

all Egyptian artifacts. This is not the portrait of a slender boy but of a

god-king, living for ever and ever. Few photographs do the mask justice: gold

is a difficult material to photograph without it assuming the consistency of

brass. The most successful is perhaps the first to be taken, by Harry Burton, the

American photographer who was present in the tomb from the time of its opening.

In Burton's photograph the mask appears still wreathed with

the garlands which were laid around it more than three thousand years before.

The presence of the flowers and the little smudges of dust which Burton and

Carter did not remove, to avoid destroying the garlands, give the mask an

extraordinary living presence.

When cleaned and cleared of the scattering of flowers the

mask is magnificent, a triumph, if not of high art, then certainly of the

highest craftsmanship. But it is clearly an artifact whereas, in Burton's

photograph, the king lives.

The impact of the discovery of Tutankhamun can perhaps best

be appreciated by comparing the finding of his tomb with the near-contemporary

excavation of the Royal Tombs at the Sumerian city of Ur by Sir Leonard

Woolley. For barbaric splendour combined with grand guignol, the great death

pits at Ur should totally have eclipsed Tutankhamun, yet they did not do so.

Woolley found a number of burials, sunk deep in what was

evidently a royal or sacred burial site, on the outskirts of Ur, one of the

most important of Sumer's city-states. The burials were much earlier than

Tutankhamun's, c. 2600 BC, and thus earlier even than the Giza Pyramids.

Altogether Woolley found sixteen burials which he believed were of royal

personages. In the stone-lined vaults, deep in the earth, were found the

remains of highstatus burials, attended by the most elaborate panoply of death.

The principal occupants of the tomb were attended by ranks of courtiers,

musicians, soldiers, wagoners (with their wagons and the oxen which drew them)

all neatly laid out, for a carefully organised ceremony of death.

The artifacts which were buried with them were of the most

superb craftsmanship, elegant, austere but at the same time extremely rich in

material and adornment. They are, it must be said, very un-Sumerian in design

and craftsmanship.

Unlike the excavation of Tutankhamun's tomb, which has never

been professionally published, Woolley unleashed a stream of sumptuous and

detailed reports on his excavations, supported by many popular publications. 7

Yet for every thousand people who know the name Tutankhamun there may be one

who recognises Ur and its royal burials, even when it carries its biblical

ascription `of the Chaldees' with its putative connection with Abraham, the

Friend of God.

The reason for the lesser impact of the Royal Tombs of Ur is

that they were not redolent of the archetypes in the way in which the tomb of

Tutankhamun was so liberally provided. Sumer, despite the fact that it is

probably the culture in which writing evolved into something more than a simple

device for the convenience of accountants, has never caught the world's

imagination in the way in which Egypt has done. Waiting in his tomb for three

thousand two hundred years, Tutankhamun was the heir to all the immense

accumulation of wonder and respect which Egypt had engendered and, in his own

person, was to be identified as an archetypal figure such as only Egypt could

apparently produce.

Tutankhamun was the last lineal descendant of Ahmose, who

had founded the Eighteenth Dynasty more than two hundred years earlier. What

has been interpreted as the marks of a blow behind his ear and a displaced

piece of bone, possibly dislodged from the interior of his skull, have prompted

suggestions that he was murdered. He left no heir though two female foetuses

were found in his tomb, perhaps his children who had been born prematurely. He

had married a daughter of Akhenaten, Ankhesena'amun, whose name had been

changed from Ankhesenpa'aten. She brings her own small element of tragedy to

the decline of the Thutmosid house. Evidently bereft at the death of

Tutankhamun, for they are often depicted, like two flower children, charmingly

engaged in simple pleasures (and she it was who scattered flowers in his tomb),

she appealed to the great King of the Hittites, Suppiluliumas, to send her one

of his sons, that he might become King of Egypt. That such a message was sent

at all is a measure both of the desperation of Ankhesena'amun and those around

her and of the state of Egypt. Suppiluliumas agreed and despatched his son

Zennanza with a suitable escort south to Egypt. He never reached Ankhesena'amun

for he was murdered on the way. Of Ankhesena'amun, nothing more is ever heard.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)